This is a work of fiction. You can read the previous chapters here: 1, 2.

The ferry crew are from the capital Majuro and everyone speaks English. We become easy friends on the passage. I am a curiosity, a source of mirth and jokes. They meet Americans and Europeans, they say, but I am the only one who swam to the islands. The captain teaches me to operate his boat. "Is it against rules?" I ask. “Who is checking? At sea, I make the rules," he smirks.

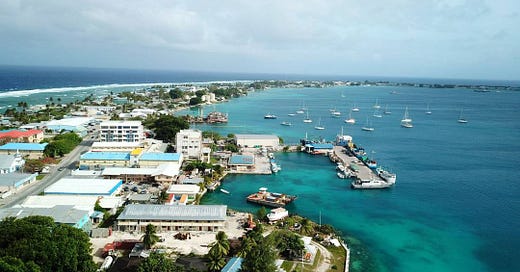

I see the Majuro Atoll after four days on the ferry. The Marshallese capital casts a band of light into the night sky from thirty miles away. By the morning, our ferry boat follows a container ship into the Calalin Inlet. The container ship sails to the Delap Dock, the main port of Majuro. We turn past the lighthouse to Uliga Dock, where the ferry company makes its home. Their four boats serve the outer atolls of the Marshall Islands. I am on one of them.

I climb up on deck. My heart is racing. I can see forward but have a place to hide. I am expecting to see Timothy Trenton, my contact from the embassy. I am afraid to see Olu, from the gun-runner ship. He would be trouble. I have no plan if Olu is there. What could I do? Fight an enormous man or jump into the ocean for another few-day swim?

But I don’t see Olu. He is not among the workers or the small group waiting for the boat. The tall man would stand out. I see Timothy in a buttoned-up short-sleeved shirt and slacks. Everyone else is in well-worn T-shirts and shorts.

The dockhands catch the mooring lines, whip them around the bollards. The action drains dockhands of energy, and they plod through the rest of their tasks. One lowers the gangplank onto the ship. The other ambles to a mobile crane and drives it closer. It is a rusty piece of equipment, a brindle of old yellow paint and rust stains. It screeches, its pulleys whine, the cables twang. It is an ugly and noisy beast.

The ferry dropped off cargo at the atolls along the service line and picked up cargo and a dozen people. The passengers queue at the gangplank to disembark. A man and a woman bottleneck the procession; their box is too wide to fit between the handrails and too heavy or awkward to lift above. The dockhands shout directives, the woman shouts back, the first mate hollers at both of them, then the ferry captain jumps into the fray. The couple resigns and walks the box back to a pallet on the aft deck for the crane to lift it over the rail, but now they must wait.

I follow the passengers off the ship. The captain is holding his hand up in the air. I return the high five, then put my hands on both of his shoulders and thank the man. He is delighted.

“Andy Baskero,” Tiimothy shakes my hand. His palm is sweaty and soft. Bids of sweat cover his thin upper lip. A sweaty mist is on his pale forehead. He smells of cologne and fresh laundry. He is gangly and young, twenties, I guess.

“Timothy. Thank you for meeting me here. You did not have to,” I say.

“I did, actually. You are technically in the country illegally, so until we sort your passport out, I must accompany you.”

“Oh.”

“It is fine. No one cares. But we have to follow the rules in case someone suddenly does. I almost asked about your luggage but that would be dumb,” he laughs. I laugh. He points at my spear.

“A gift from a friend on Namu," I say, "I had to earn my keep on the island.”

“I am not sure if we can have this in the embassy. It is technically a weapon. Are you attached to it?”

“I would love to keep it. It is the only thing of mine I have left,” I surprise myself with the answer, but he nods.

“No worries. How about it becomes 'mine' for a short while. I can store it in the embassy. Are you hungry? Craving anything?”

“Greasy Chinese food?”

“Did not expect that. I expected a burger.”

It irritates me. “Yeah, odd craving. No Chinese around here, I’d imagine?”

“Sure. The best place was right here on the Uliga dock. But it burned down. They re-opened not too far. Huge menu. Hai Shien. We can go.”

“Crowded place?”

“Sometimes. There are no cruise ships in town, so it won’t be a zoo.”

“I have not been around a lot of people at once for months now. I am wondering…”

He waits for me to finish, but I trail off. He nods and leads me to his car. We stuff the spear with one end at my feet, and the other extending past the back seat and against the rear window. Timothy wraps a towel around the sharp tip.

“We can order take out. But let me check in with the embassy. Protocols and such.”

He calls, listens, nods. “Ok, heading that way. Hey, a favor? Get some take out from Hai Shien?” He turns to me, “any idea what you would order?”

“Hunan chicken.”

“They want us back at the embassy,” he says and starts the car.

The car is sweltering. It smells of heat. The nauseating stench of hot polyester and old french fries drags me back to the rush hour traffic of my younger days in Washington, D.C,. Smells of home. The air conditioner whines, chokes on the humidity. I wipe the sweat off my forehead.

"It will get cooler, or rather less hot in the car," Timothy says." When the newbies arrive from the States, we keep them indoors for a bit then slowly let them get used to the heat. It is next level here. But you are used to it with you time on the outer islands."

"Was never this hot on Namu."

"It is the concrete. And no breeze, but eventually you get used to it. Although, I don't imagine you would have the need since you probably will stay for a few days at most. Once your passport is approved, you can fly back with the repatriation papers. Don't even need to wait for the passport to arrive."

"Why does it need to be approved? I mean I had an active one, just lost it."

"It is not that simple. We have to ascertain your identity and go through the repatriation process. Busy work mostly. But you have no idea what people do to get to the US. We have seen every scheme. I am not suggesting you are running a scheme. But the process is inflexible, so we would be going through all of it. It is mostly just annoying for you. For me it is someone new from the States to talk to, there is not much chance otherwise."

I don't recognize this man. He had a reserved demeanor on our check-in calls but now his speech is a torrent. Professional on the calls, friendly, in a cool, customer service way. Now effusive.

"Sorry, the traffic here is slow," he goes on. "So few people own cars, most can't afford them, but there is only one road, practically, on the thirty mile island. So everyone with a car drives it. Slowly."

We pass dilapidated buildings painted by a hurried hand long ago and by rust for years after. We pass a wrought iron fence, ornate and black, protecting a white blocky building. 'A convention center', Timothy points. Then buildings in pastel tones of purples, reds, and blues. Each looks good from a block away but up close reveals broken gutters, flacking paint, and rusted cages over the cracked windows. A few buildings are pristine. The next few are boarded up. We pass a school, ‘Delap Elementary’, the sign says. It looks nice. The Church of Ascension with an open-air concrete basketball court under a poll barn roof without the barn walls. Two kids are tossing a ball. Then we are back to a dilapidated block of boarded up homes.

"Why so many boarded up building?" I talk over Timothy. I stopped paying attention to his jabber. "Sorry," I say, "it is just jarring how many buildings are abandoned.

"Some are not abandoned. But people are leaving. A third of the population moved to the US to work and live. Honestly, it is not a bad thing long term."

"Not a bad thing?"

"The islands are less then fifteen feet above the sea level. In a fifty to a hundred years, or less, if you look at some models, they will be underwater. Or they will be underwater when a typhoon passes nearby, although we are outside of the typhoon belt here, but still affected sometimes with the swell and winds. So every foot of the sea level rise elsewhere, for these islands, is three. People away from the coasts don't understand that, but here they do. Yet, they are not leaving because of it. The climate threat it is still too far away to imagine. Though it is one generation away."

"Why are they leaving?"

"Are you from a big city?" Timothy asks.

"Both."

"What do you mean?"

"Grew up in a small town, a village basically, in rural Virginia, and in a big city, too. In DC."

"Ah. I am from a small town. Two thousand people. Those who choose to stay in a small place, have a known trajectory. You know what you will get. You know who you will be. But if you want more than a simple predictable life, a job your father had and a wife from your own high school class, then the only option is to leave. I think it is the same here. Marshallese are people like all else. Same ambitions. If you are young especially - excitement, partying, opportunity, money."

"That's not what I have seen."

"On Namu? I heard the outlying islands are different."

"Have you not been?"

"No. Outside of our mission. No way to get there and back in a reasonable time. I mean a trip for lunch or something when the plane flies out there. Is it worth it?"

"There is no lunch."

"What?"

"No restaurants."

"Oh."

"Yeah."

"Were you bored out of your mind?" Timothy looks at me with compassion.

"For once I was not." I say then think. "I felt fulfilled."

"Fulfilled? Why?"

"I don't know. Maybe... Hmm... I'll have to think about it."

A man on a motorbike passes us on the right. We are on a single lane road without a shoulder. People are walking on dirt path a foot way from the asphalt. The biker rides on the grass in-between and zooms past us. My heart jumps in my throat. The walkers hardly move. The bike’s wide tire kicks up dust, then it is back on the road. The front wheel hits a pothole, the handlebars wobble, the bike swerves then recovers. Timothy talks through it all.

I think of Leroij on Namu and her certainty that Niko would return. I understand. I don't want to be here. Not anymore. She said Niko and I were cut from the same cloth. We need the freedom of the sea. Maybe. Now, I want to go home. My home in a busy Boston, but in my quiet neighborhood where I never have to drive.

The embassy is a low lying compound, beige, with flag poles lining the fence from one guard shack to the next. A marine at the entrance waves at Timothy, leans in to look at me, and asks if I am ‘that guy’. Timothy nodes and the marine lets us through.

The inside is frigid. I shiver.

“The thermostats are set to seventy eight degrees inside, but after the outside it is like a meat locker in here." Timothy points to the ‘Official Personnel Only’ door, past the consular windows. I follow him through a corridor into an empty office. A large window is facing the courtyard in the back of the building. Chairs are arranged in the shaded patch under the palm trees, a living fence is behind them, then the wrought iron fence with razor wire spiraling along the top the entire length of the visible segment.

I settle on the brown leather couch. It is firm and crisp, uncomfortable in the way unused couches are, cold against my bare thighs.

“Madam Ambassador wants to welcome you.” Timothy sits in a leather chair by the desk.”

“Ambassador? I gained some notoriety,” I joke.

“Not much happens around here. Well, not true. Too much, but much of the same happens around here. People are curious about your story. Plus, the ambassador feels it is her duty to welcome a rescued mariner in distress.”

The ambassador is a petite, wiry woman. She beelines towards me from the door. Timothy springs up and I do too. She waves Timothy to sit down. He does not.

“Ambassador, Currie,” he says.

She waves him down again.

“I just took over the post,” she tells me, “everyone is too formal.”

“You have a fearsome reputation, Madam Ambassador.” Timothy says without a hint of levity.

“Mr. Andy Baskero. Welcome to the United States embassy. Your story is an interesting one. I hope you can share it with us over the next couple of days.”

“Andy is fine, please. Not much of a story besides swimming, fishing, and learning the locals ways.”

“I suspect it is a good story, Andy.” She motions me to sit on the couch and sits down on the other end of it. “In three days, we have a reception for the US expats: embassy staff, NGO workers, some private business reps. Please join us. We already did most of the background work to get you home, but you are stuck with us for a week or so. Also, our colleagues from other services expressed curiosity about your travels. So, they want to debrief you today. I am sorry. I suspect you rather relax and explore the local scene. Let’s hope they are quick.”

“Debrief?”

“In a manner of speaking.”

“Colleagues from where?”

“Homeland security. It is fairly standard.”

“Better than CIA or something sinister.”

The ambassador laughs. “Well, I wanted to meet you to let you know that we are here to help.”

“And the colleagues?”

“I don’t know what they are up to.”

“Of course, you do.” I smile politely.

She smiles politely back. “Of course, I do. Drinks in three days, Andy. I want to know about the outer islands. Truly. Timothy, please finds us one hour in two days, one hour.”

We stand up. She shakes my hand. Timothy leads me through the corridor into a smaller office with his name on the plaque. A desk, two chairs, large and comfortable. The chairs are facing each other, five feet apart. Timothy points to one, then leaves to get the ‘colleague.’

A standard process, I convince myself. A guy washes ashore out of nowhere, someone has to confirm the story. Do some checking. Nothing to worry about. No, nothing to worry about.

The ‘colleague’ is young. I stand up when she walks in. She is my height. Her face is delicate, feminine, with a small but broad nose and full lips, thin neck that joins muscular traps. She is in a sleeveless white fitted blouse. Her shoulders are wide, with developed deltoits, and cut muscular arms used to weights. A body of an athlete, a hundred meter sprinter, or maybe a cross fitter. She exudes physical power. Thin waist. I smell her deodorant and a hint of sweat that gives shine to black skin. I feel a growing erection.

“Mr. Baskero,” She extends her hand. Ringless, delicate fingers. I shake it. I feel the calluses of a weighlifter. Her shake is moderated as not to crush my hand.

“Yes, I am.”

“April Clemens. Agent Clemens in the States, but April is fine here.”

“Why is it fine here?”

“Everything is relaxed on the islands.”

“True. Slower life. How long were you here?”

“Three days.”

“New assignment?”

“In a way, I work repatriation cases. Not sure how long I will be here. I travel a lot. Anyway, I am sure you may want to rest, so let’s get through a few questions.”

“Okay.”

“I read the statement you provided in the email to Timothy Trenton. So if we can confirm a few facts? You experienced a catastrophic fire. Three and a half weeks prior to your landing on Namu atoll?”

“Yes.”

“You escaped the fire by deploying a life raft?

“Yes.”

“You were in the life raft for three weeks until it also suffered a catastrophic failure. Then, you floated in the ocean currents for three days, until you swam to safety through an opening in the barrier reef, where you met the locals. How was your condition at that point? I imagine you were haggard?”

“I was not in the best state, no.”

“Do you recall your position before the boat fire?”

“Not exactly.”

“But you have an idea.”

“Sure. Yes, you have to keep track at sea.”

She waited for me. I waited for her.

“You are a journalist, right?”

“More of a writer, but yes, I wrote features for magazines.”

“Have you worked undercover?”

“What?”

“Have you joined any groups that you researched in the past? You did pieces on art trade, exotic animal trade, catalytic converter theft, illegal fishing, climate actions. Impressive resume. So have you joined any of those groups that you wrote about? For research?" She adds.

“No, I have not. What is this all about? Do you research the work of all repatriation cases?”

“No, other people do, check people out, then I get the non-standard cases.”

“I am non-standard?”

“I don’t know if you are, but your case is. Mariner in distress missing for three weeks.”

“Could I see your identification?” I ask.

“Seriously?” She laughs. “Can I see yours? Maybe a passport?”

“Could we have embassy staff present here?”

“I am embassy staff, and you are my guest. But let me get to the point. Your last location was east of French Polynesian islands by a few hundred miles. In the Southern Hemisphere. We had AIS location pings from your boat, and you helpfully used a personal satellite tracker to share your real-time position on your social media account. They all stopped reporting on the day you stopped communicating with your family. There is not a way to get from that point in the Southern Hemisphere to Marshall Islands on a raft. They are in the Northern Hemisphere a thousand miles away. The currents do not flow that way, and the wind does not blow that way. So I am curious as to who gave you a ride, how you ended up back in the water, and why you are not telling us about your time with your sea friends?”

“I already provided my statement.”

“You have, but it is not yet official. Once it is, and if it is untrue, and it is untrue, then you are breaking a federal law. A number of them in your case. I rather have an actual story.”

“What are you suspecting me of doing? You can confirmed my identity. I am a US citizen.”

“There is little doubt that you are Andy Baskero of Boston, Mass.”

“So?”

Agent Clemens, leans back. She is no longer April, and I no longer have a growing erection. I am afraid of her.

“Let’s stop fucking around, Andy. I know you are a victim of bizarre circumstances. I need your help, and you need mine.”

She pulls out a stack of photos. Lays them out, in front of me, without saying a word, one by one, and watches me. I don’t know any of the faces. Some are hard to see. Then I recognize the Phillipino man from the fishing boat galley, the one with fake teeth. I try not to flinch but she picks up the photo and sets it aside. A few more men I don’t know. Then Olu. I keep still but she sets him aside as well. I don’t know the rest.

“We have been tracking a few boats. One was in the area where your boat has gone dark. Then it traversed the ocean and passed by Namu Atoll a couple of days before your re-emergence. So I presume that was your ride. I also suspect that you are aware they were not just fishermen, or why else would you omit this part of the story?"

I shrug.

"Stick to the story you told Timothy whenever someone asks. You are not in trouble, Andy.”

“What do you want from me exactly?”

“We would like you to help us identify other men from that ship.“

“Why were you tracking that boat? Of all the boats in the ocean?”

“I can’t tell you that but you already know. Just don’t talk about it.”

I sit and think, and she let's me.

“I think, I am in danger.” I can't find a reason to hold back.

“I don’t think you are of much interest to these men, Andy. I would not worry about it.”

“This man,” I point to Olu's photo, “flew to Namu on a Cessna Caravan.”

She is dumbfounded. “You shitting me?” I shake my head. “Did you talk to him there?”

“No, I saw him through the trees and sailed the outrigger canoe to other islets, hoping he would go back with the plane. That’s what happened.”

“You think he went there for you?”

“No other reason to go there.”

She thinks for a bit. “Mother fucker! That is great, Andy.” She jots a note. “I don’t think you are in danger here on Majuro. But you should stick with me for the next couple of days, anyways. I am a good company.”

“That’s not the sense I got over the last few minutes.”

“Like I said, you are not in trouble with us.”

The embassy staff stays in DUD - Delap-Uliga-Djarrit district. It is a developed area with a secure neighborhood, Timothy gave me a rundown yesterday, on the drive over to a duplex the embassy assigned to me for the next few days. April is staying on the other side of the same duplex. She spent the short drive typing on one phone then on the other. One government issue, the other private, I assume.

The rooms are sparse, with a bedroom, a small kitchenette to make simple meals or reheat a take out, adjacent living room, a single bathroom with a shower-bath combo. Sparse!? Maybe in my old land lubber life but a luxury after the adventures of the last months. There is a laptop on the desk with a note ‘Unsecured - not authorized for official communication.”

The room is set to seventy eight degrees, same as the embassy. The temperature would be balmy in my house in Boston. Here it gives me chills, covers my skin in goose bumps. I don't like it, I rather open the windows and have the heat, but the windows are sealed. For security, I assume.

I run the shower and turn the water hot. I think of the last time my body felt the high pressure stream. In a Mexico City hotel for which El Universal paid. The paper invited me for a panel and two talks. So long ago, in a different life, but only four month in the past. My god. The sea and the islands disengaged me from time.

I love the pressure and the burning heat of the shower stream. A pointless luxury which I did not know I missed in the heat of the tropics. Yet, the walls of this cold duplex sever me from the world and cuddle me with the new comfort. I feel the hedonistic joy. I want more. It is the cycle of desire without an end. Yet, all I need is the sea, my spear, and a friend. And a lover.

Maybe I need prestige? Recognition? Validation measured in letters and comments I receive for each article I publish? Is it why I am rushing home? I have not thought of work since my boat burned and stranded me, severed me, freed me from the demands of the achieving West. And I have not thought of achievements until the luxury of the hot stream caressed my body. This shower. The coolness of the room. The catered food. I know I need none of it. But I feel now that I want it. Then I don’t. I don’t want it. I want none of it. I want a peace of mind. Yet, I stand under the shower head and, as the water turns colder, I turn the handle lower to keep the stream almost scalding hot. I am lobster red and weak from the heat. I stumble out with a towel around me and in a daze I plump on the couch. I loved that shower, and I hate myself for it.

I want to sit and empty my head of thoughts, but they are rushing through me. The facts from April shifted my understanding of what is happening but everything is only a nebulous speculation. I need to research. I ought to let it go, and make it home to Boston. But I am a journalist, a reluctant one, who prefers to think of himself as a writer, but sleuthing is in my genes from my absentee war-reporter farther, and in my mind from years of work for the magazines. I know I won’t let it go, until I understand more.

Fuck it. The laptop turns on and opens without a password. It is unsecured all right. April could find out what I am researching if she wanted to but what is the harm. I am looking at public knowledge. I will face her tomorrow.

Who is selling weapons to whom, and why does US Homeland security care? Are the weapons for terrorists? Unlikely. The shipment seemed too big, official, although covert. The crates were not the small potato assault weapons but something much bigger. Shoulder launched missiles?

I search for armed conflicts in this quadrant of the planet. China and Philippines have been at each other’s throats over the control of the Second Thomas Shoals. They are not firing shots but the tensions are building. No, US has official defense agreements with Philippines. I read about the Mutual Defense Treaty from 1951, then Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement treaty from 2014. A boat full of illicit crates would not make a difference where formal arm sales exist.

In Myanmar, the leading junta is fighting three groups. Some are supported by China, others are looking for Western support. I don’t find official Western support for anything in Myanmar, so if the West is involved then it is through proxies, or in Iran-Contra style. But if it is proxies then the Homeland is probably on it, or rather aware of it. Unless the information is compartmentalized and the right hand does not know what the left hand is doing. How would they know what ships to track? I have no idea.

I am making assumptions, inventing dubious possibilities, which, given enough time to sit around in my head will turn into imagined truths - conspiracy theories becoming false facts.

I close the laptop. I am out of my depth and should leave this along, yet, I can’t get April’s words out of my head. ‘That is great, Andy,’ she said. Olu came for me, and she thought it was great. A fucked up reaction. She thinks I saw more than I did, and thinks they came for me because of it. But I know practically nothing.

In the morning, I make coffee and sit down at the table to sip it, but see April by the back sliding door with her own cup of coffee and a spiral notebook. She knocks and waves the notebook for me to come out, and a big, thick pen, the kind young girls in my elementary school used to color, slides out of the spirals and smacks the concrete patio outside. I open the door, pick it up. It has four sliders for four different color inks. I hand it to her, but her hands are busy with coffee and the notebook, so I slide it back into the spirals.

“Join me?” She asks.

I follow her to a table and cheap plastic chairs on her concrete patio. She is in short shirts and a loose tank. Her calf muscles and the quads ripple as she walks. The legs are muscular, strong, captivating. She sits down, and crosses one leg over the other, and I watch the IT Band flex as she sways her foot.

“So what did you find?” She asks.

Should I act perplexed or indignant? I surrender instead.

“A conflict in Myanmar,” I say, “The junta and three separate groups are fighting each other, getting their arms from somewhere. Well, some from China, but others - who knows. Maybe us?”

“Us - as the United States?” She asks.

“Should you be monitoring my Internet searches?”

“So what do you think? Us as in the United States?”

“Not directly. But maybe through proxies, enough of them to cover the provenance of whatever weapons are sold.”

“What did you see on that fishing ship?”

“Just crates. Olive drab, 6-8 feet long, wooden. Black markings in Latin alphabet but did not have to be English. Rockets? Missiles? What was it?” I ask.

“I would like to know. Why would the US sell it to Myanmar? Or a party there?”

“Same old influence play, I'd guess. China is there, they are vying for control. We can never let it lie, worry about the regional stability and conflict spillover effects, the same old bullshit ‘domino theory’ in some new clothes pedaled by the same think tanks. But, of course, officially it would be humanitarian reasons for us doing something, if an inquiry is ever started.”

“You are cynical man.”

“I am a journalist. How else could I be?”

“Is it what you think?”

“That journalists are cynical?

“That the US is supplying arms to counterbalance China in Myanmar?”

“No, I don’t think that.” What I think is a guess, and I don’t know why she is asking. But she waits for me to talk.

“Listen, April. I don’t know anything beyond seeing a bunch of crates and researching on the Internet for twenty minutes? Why are you asking me something you already know?”

“I don’t already know. So what do you think?”

“I think our allies are selling weapons under the table that US sell to them. The allies maybe not selling them, but some crooks in their military. They have no ambition beyond lining their own pockets. The US cares, because if those weapons blow shit up in a wrong place, it could be an egg on the face, or worse. Some serious diplomatic crisis.”

“Pretty good.”

“Is it what you think?”

“Better than if it is our people selling arms through proxies. Would it not?”

“Do you really not know?”

“I don’t. I am not that kind of agent. Why do you think it is about weapons?”

“You said you tracked those ships, and you came to interrogate…”

“Debrief, “ she corrects.

“Yeah…debrief me. I can't imagine you are worried that a small fishing vessel is exceeding their halibut quota. Can't be a coincidence that the ship I was on had olive drab crates.”

She nods. Sips her coffee. I sip mine. Her hair escapes the hold of the hair band and swings forward in a tight long curl to the side of her high cheek. She sweeps the strand behind her ear. The arm muscle flexes beneath the glistening skin. She stares into her cup and taps it with the long fingers, sways her wide foot in a flip flop, and with each sway I watch the IT band and the quadricep pump like a heart.

“Something wrong with my leg?” She asks after a while.

“Sorry. I was lost in thought.”

“Man’s legs - a partner once told me.”

“Strong and beautiful. Not men’s legs.”

“Strong and beautiful. You are a charmer. Can physically strong be feminine?”

“I am sensing a trap.”

“No trap. A serious question.”

“I don’t believe in a feminine ideal. Or a description of ‘sexy.’” It is an attitude. A matter of self-perception, maybe.”

“My father wanted me to be a strong woman. But not in the way of my body. He did not think women should play hockey, lift weights, box, or carry guns on the front lines. Vestige of his generation.”

“Did you change his mind?”

“No. He died five years ago in an industrial accident, was almost seventy and still working. He would find me hideous today.”

“Hard to imagine.”

“That is what I imagine, but, I suppose, how I see him is colored by old hurts.”

We sip our coffees. I take a chance.

“You think I saw something important. That’s why Olu came back for me.”

“Was Olu the name of that big man?”

“That’s what he said, but I assume not.”

“Not something. Someone. Who was on the ship, besides Olu, worthy of a mention?”

“The Captain. Captain Ahab, he said.”

“As in Moby Dick? Any inkling on his actual name?”

I shake my head.

“Did you speak with him?

“We had dinner every other evening. Talked about everything, mostly literature.”

“With the captain of a fishing vessel?”

“He said it was a temporary assignment?”

“Assignment?”

I nod.

“Seems like you are willing to help?”

“I just want to get home. Maybe this is the fastest way," I wait for her to speak, but she sip her coffee. "There is one thing, I don’t understand. It was the Captain who advised me to jump ship and suggested the location. Olu was in the know. Why would they want me back?”

“May not be their decision. You made the news in the papers. A mistake, by the way, but, I know, not of your making. Anyway... Timothy will be here soon to take us shopping. You need something for the reception in two days and for the regular wardrobe. We can pick up the conversation tomorrow. Another cup?”

I nod. She takes my cup, refills it inside and hands it to me.

“What happened to your partner, the one who said you had man-legs.”

“Still married to him. He is a good friend.”

“A good friend?”

“And sometimes a lover, but mostly a husband. We make each other better, but we live our separate lives.”

“I would like to know how it works.”

“Very well, once you no longer possess the other.”

Timothy is called to the embassy, and the shopping plans are remade for another time. Next two days are slow waiting. I take two showers a day, read about the islands, write notes on my trip, read about the arms trade, legal and illegal. I message with my editor on the feature to extract from my time at sea. Our ideas do not align.

During our morning coffees, I complain to April about his lack of vision. She complains about how little she sees her friends, and how little in common they have with the friends absorbed by their new families and children. We banter about mundane things of lives as the formality of our first meeting eases away.

The second afternoon, Timothy drives us to the tourist district, where the boutiques cluster to serve the cruise ships. The shopping is a light-hearted competition between April and Timothy. They curate the clothes. I put them on. They argue like judges on a pop-culture fashion show, and thumb up or down each other’s choices. I don’t get a say. Timothy is winning. They are enjoying it. I want to hate it but I am caught up in their energy.

They banter about fashion, ask me about the way of the islands, how I felt among the people. April sets a panama hat on my head, steps away and nods. Timothy is unsure. I set the hat back. April tries another on me. They both nod, but I set the hat back. They banter about music and the latest of the celebrity tours, ask me about my musical tastes. Seventies rock? ‘You are old,’ they declare, but approve my affinity with jazz, and are properly stunned when I name a string of EDM DJs.

I buy two pairs of shorts, three loose buttoned shirts which work best for the heat, a single pair of pants, per Timothy’s insistence, casual but appropriate for the upcoming reception. And a pair of slip on shoes.

We settle at a bar of an outdoor restaurant. I order a rum cocktail, but they decline. They are on the clock. I am not. I exhale an exaggerated sigh of orgasmic joy with each sip of my Painkiller. They make a pact to keep quiet about this lunch, then order their own Painkillers.

We laugh. We drink. We joke. We are three friends having lunch.

We take turns telling stories from college, work, private lives. Timothy taps the table to emphasize his plot points. April taps my forearm telling of her ocean time in the navy. She squeezes it, gently, telling the story of her navy crush. She is thirty six, I learn. I guessed twenty eight.

The embassy reception is in the palms shade in the courtyard. Hanging sun sails cover the space in-between the trees. The heat bothers no one, most have been in the tropics for months. It does not bother me, but my new cotton pants and buttoned shirt do. They are loose and should be comfortable but the sensation of something touching my shins distracts me.

The ambassador pulls me along for the rounds of introductions. Timothy is by our side. April is watching from the bar, always talking to someone, but I catch her glances, keeping tabs on me. In a half an hour I am free. I have my third Champaign flute and feel the pleasant, light-headed sway.

I stand by the bar and watch NGO workers, business people, and the embassy staff in a power polonaise to curt a favor, gain access, or paddle influence. I never learned the currency of power, the art of politicking. That disease of the civilization, or the driver of it, I don't know, but a brake on my career.

“Have you had much to drink on Namu?” April takes my elbow.

“No, but catching up today. And it is catching up with me.”

“I wondered.” She follows my gaze. “That’s Giles.”

“Met him in five days here?”

“We talked a bit while you made your ‘met the adventurer-hero’ rounds. Is he a good looking man?”

“He is a good looking man. Do you think he is a good looking man?”

“I do. But I am not his type.”

“He said that?”

“No. His eyes followed your ass without interruption. Impressive that he kept the conversation going.”

She leads me to the table by my elbow. Giles just sat down with another woman, but stands to shake my hand.

“Join us,” he says, “Maria is my ex-colleague. We worked at the school together.”

“Quite a story. Marooned in the ocean.” Maria’s voice is raspy. “Sorry just getting over a cold. Get one every time I fly to the States.”

“What school?” I ask.

“The Ascension Catholic school on the island. The main school, really.”

“Where are you working now.” I ask Giles.

“Marshall Islands College. Teach history and literature. Same thing I did at Ascention but without the censorship.”

Maria laughs. “The school frowned on the history teacher’s,” she points to Giles, “rather cynical view of the Catholic history.”

“Kids need to be taught the truth.”

“I think you were settling childhood scores.”

Giles shrugs. “A bit of that, with the now-dead nuns of my Saint Louis school. I had enough of their shit then,” he smirks.

“Why would you work in a Catholic school then?” April asks.

“The only option. I was on the islands when in the Navy years ago. In Majuro too. Changed my life. Remember thinking, these people are so fucked. Wanted to come back and make a difference. I was more naive back then.”

“A bit colonial, Giles?"

“Colonial? You mean, the white man comes to the islands to save the locals from themselves? No, not that. It’s the climate change. These islands are doomed, and soon. I wanted to teach so the kids had a lag up when they or their kids will not have their own land to live on. The colonial is the Ascension School. Marshallese have a beautiful culture, and a rich way of life. But first, we chipped away at it with our god, and now we take it away with our greed, drowning their future.”

“Giles has passionate views,” Maria laughs, “they did not sit well with the rector. The college is a better place for you anyway.”

“Would be for you too. You agree with me.”

“I see the bigger picture. The Catholic Church bankrolls the school. The empirical education there is the best on the island. So I look at that.”

“Catholicism has been here for over one hundred years,” April says. “In how many years does something foreign become a part of the local culture?”

Giles shakes his head. “If you remove the active church influence, and the money from abroad, the Church here will wither."

“When I was on the outer islands,” I say, “the matriarch there, Leroij, was brought up Catholic, thinks of herself that way. But her views are an amalgam, with bits from everywhere. Isn’t it how cultures evolve? Mixing of ideas birthes something new, then after a generation or two, it is the culture.”

“Catholicisms is not compatible with Marshallese,” Giles says, “The traditional society here is matrilineal. Leroij was the matriarch, you said. That does not sit well with the patriarchal Catholic notions.”

“I don’t defend any religion. Religion is a reactionary force that, I hope, will recede from society someday. But Catholic influence here is a fait accompli. Would not purging the elements already integrated into the local culture be an act of violence against it? The culture of the current generation?”

“We try to remove invasive species from native habitats."

“This is not a habitat, Giles,” Maria sighs, “and who appointed you the gardener?”

“Not what I meant. Sorry. The point is if I am teaching history, and religion has shaped it, and it did so through violence, inquisitions, and expulsions of Jews, I think I should teach that.”

“And they let you do it for a time. But, let’s be honest. Your unfortunate, and public, joke about Catholic priesthood being a pedophile gay club is what severed the ties.”

“Yeah, well.”

“What do you teach, Maria?” April says.

“Mathematics. Algebra, geometry, trigonometry. And a chess club.”

“I loved math in school.”

“You are a rarity,” Maria laughs, “but I have a couple of kids that love it. They make it worth it.”

"I thought you would drift off with Giles by the end of the night," April smiles. Her smile is carefree, relaxed by Champaign and a martini at the reception.

We are on a duplex patio, back at our residence. The scorching heat lost its bite with the setting sun. What's left of it can longer break sweat on our skins. The champaign buzz keeps me smiling but does not insist on swaying the inside of my head.

"Two bottoms do not make for the funnest night."

"Bottoms and tops as in who takes it and who gives it?"

"That's right."

"Can't you switch off? One way, then the other."

"Some gay people flip, others enjoy either position, but many stick to their preference."

"Similar to submissive and dominant dynamic in the BDSM and kink scene, I suppose"

"Is it your gig?"

"No, my husbands. I tried it but could not take it seriously. Seemed like an acting class."

"How do you work it out? With your husband, I mean."

"An open relationship. We still love each other. He is a good human, but we want different things. So he has his kinky lovers. And I have my job."

"Uneven trade. Or maybe you don't see it that way?"

"It is a good trade. I have my lovers too. But my work takes me all over, so he lets me go to do what I love, I let him live out his passions. We are more together now when we are in the same room."

"I don't know if I could do it. There is jealousy and fear. If my partner slept with others, I'd fear an emotional connection growing between them. Could tear the relationship apart. Why invite problems?"

"So, you chain another person to you, and keep them around by keeping everyone else away?"

"I don't see it that way. Isn't it by agreement the partners give up a bit of freedom to commit and offer a sense of security?"

"Or you could give another person all the freedom they want, and be the someone who they choose to be with and want to be with. And not because they are forbidden all other options."

"When you put it that way," I smile. I want to make the night lighter without the argument and stress. But she is relaxed, joyful in asserting her views.

"I though about it earlier on, when my husband and I were discussing divorce. In the "enlightened" Western world," she air-quotes, "if I tell you who can be your friends, or what job you can and cannot have, I am a control freak. And that's out of vogue. It is wrong. You need to let the other person be who they want to be. People agree on that, at least in the progressive cities. Not so in the Bible Belt, where I come from. Almost with everything we are told to give another their freedom, except for sex. Here, a partner has a right to assert control. Why is that?"

"Why is that?"

"I hear of evolutionary imperative to ascertain the gene survival, or some nonsense about masoginistic morality from a book thousands of years old. I can't find a rational answer in the context of other expectation we now have about individual freedoms. Letting people be who they are. So, it is fear. Like you said."

"I did not expect this conversation. With you trying to recruit me as an asset, and all." I am serious, but she bursts into laughter.

"I don't recruit assets," she keeps laughing. "I am a psychologist. I look into people with questionable associations who want to get into the US. My job is to tell those who recruit assets, whoever those people are, if you can be trusted in any way whatsoever."

"Can I be?"

"No. Well, yes. I believe you are a hapless victim of circumstances. You can help identifying people we don't know about. Looking at pictures. But no, not an asset."

"You are deflating my ego."

"Doing you an enormous favor."

"What's next for me."

"You get your passport, and go home. Maybe after looking at a few more pictures."

"What is next for you?"

"I am going to bed to lament how such a beautiful man as you is unavailable to female kind."

"Now you are inflating my ego... I am available to female kind."

"Bi? I thought so, the way you devoured my legs. Sadly, this is a line we should not cross. Not while, I am responsible for you."

She stands up, leans over, and kisses me on the lips. A quick kiss, but I feel a brush of her tongue. I watch her sway away, muscular legs flexing.